This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

A recent Jeopardy contestant lit into the show, claiming that it isn’t really all that good a measure of a player’s intelligence. He’s got a point—but not the one he thinks he’s making.

But first, here are three new stories from The Atlantic.

Passing the Test

A series of viral Facebook posts by a recent Jeopardy contestant named Yogesh Raut have caused something of a minor kerfuffle among watchers of the show. Raut, to put it mildly, is unimpressed by the intellectual level of America’s premier game show. He won three games, but after the episodes began to air, he went online to argue that the show’s status as “the Olympics of quizzing” is undeserved.

This all puts me in a bit of a pickle. I am a former Jeopardy champion (I made it to the 1994 Tournament of Champions and the 2005 Ultimate Tournament of Champions) who no longer likes the show very much. I wrote a year ago that Jeopardy has made some serious mistakes—chief among them ending the rule that winners step down after five victories—and should probably wrap up its legendary run. But Raut is wrong about what it takes to play Jeopardy.

So though I think the show should be retired, let me suggest to you three ways in which Jeopardy really is a test of your brainpower.

1. You need to be well-read, not well-educated.

The one place where I think I can agree with Raut and other critics of the game is that you do not need a lot of formal education or deep knowledge of any particular area to succeed at Jeopardy. After all, one of the greatest players of all time was a New York City cop. I have three graduate degrees, including a doctorate, and I got smoked by a librarian in my first tournament. (Some players theorize, in fact, that knowing too much about a subject can paralyze you; I have seen doctors and lawyers fumble questions in their area of expertise.)

You don’t need a Ph.D., but to do well at the game, you should be a voracious reader, which is how most people gain (and, more importantly, retain) facts and knowledge. My mom and I would watch the old daytime 1960s version on school snow days or when I was home sick, and she was a pretty sharp player—with a ninth-grade education. But my mom and dad were both readers; our house was full of books and magazines and newspapers.

Indeed, in my experience, people who approach Jeopardy as a test of formal smarts can really stink at playing the game. At my 1993 tryout in a big hotel in Burlington, Vermont, about 160 people walked in, as I recall, and about 15 of us walked out. The people who showed up with almanacs and atlases and fact books, the serious people whose eyes glared and nostrils flared at anyone who talked to them while they did some last-minute boning up … well, they all got turfed instantly. The rest of us had a grand old time, got our I passed the Jeopardy test! buttons, and went home to wait for a call from Los Angeles.

Now, I will grant you that getting things right does not mean you know a lot about the subject; it only means you successfully associated a clue with a fact. In one of my games, I was behind, and so I went for some high-money clues in “The Violin.” I was a young professor in security studies, so this did not seem like a natural choice. My then-wife was in the audience, and she turned to a friend in panic: “What’s he doing?! He doesn’t know anything about violins! Did he think it said Violence?”

And yet, I’d learned in my high-school stage band what pizzicato meant, a lucky break that helped me rack up some cash. That’s how you play the game.

2. You need to understand clues and riddles.

Jeopardy isn’t only about knowing stuff. You need to have a particular kind of intelligence to play the game, an agile mind that can not only recall factoids but also parse the game’s sneaky way of asking you for information.

One of Jeopardy’s favorite tricks is to firehose the player with a lot of extraneous and irrelevant detail while putting the answer right in front of you. I am making this up as an example, but a typical snare would be something like this: “A giant ruby was given to the Black Prince by Pedro the Cruel in 1367 and sits near a river of stinky and cold water known for its unusually shallow depth of 20 meters in this British capital.”

If you’re a nerd who overthinks everything and wants to show off your smarts, you’re standing there trying to unravel who the hell Pedro the Cruel was and which river is shallow and …

If you’re a Jeopardy player, your brain filtered out everything except “this British capital,” and you buzzed in and said “What is London?” while Brainiac over there was still trying to figure out who was in charge of what in the 14th century. You might not think that’s a form of intelligence, but when two other people are slamming away at their clickers and you’ve got a fraction of a second to recognize the real answer, your mental hard drive better be solid-state and super fast.

3. You need to combine intelligence with presence of mind—and never panic.

Raut is upset that the producers choose people who are telegenic. Having watched the show for many years, I think that’s nonsense; there are plenty of contestants who are not, shall we say, camera-friendly. What the producers do guard against, I learned, are people who freeze in front of a camera. (In Jeopardy lore, this is called “going Bambi,” like a deer caught in the headlights.)

Good Jeopardy players never let anything get inside their head, and the best of them pay almost no attention to the other players or even to the host: They read the question and decide whether to buzz in. I disliked super-champ James Holzhauer for many reasons, but his background as a Vegas odds guy meant he played the game with ice-cold ease, and that matters—a lot.

Full disclosure: My first Jeopardy run ended when I made all of these mistakes at once. At the end of the first game of the 1994 Tournament of Champions, the clue was “The last king of the Hellenes, he was the second to bear this name.”

Piece of cake. I’m part Greek, spent summers with my grandmother in Greece. Had a lot of drachmas in my pocket with the former king’s name on it: Constantine II.

And then panic and doubt crept in as the Final Jeopardy theme began its death-clock countdown. King of the Hellenes? Did they mean the ancient Greek empire? The Athenian alliance at Delos, the one defeated by … no, wait, I think that was a democracy, but … it’s Alexander, maybe? Were there two?

We all went for the Alexander bait, and we all lost. But my opponent made a smaller and smarter bet than I did, and that was that.

Look, I think Jeopardy has become too professionalized and too soulless. It’s lost the charm that made it an American institution, and frankly, I don’t much care for Ken Jennings or Mayim Bialik as hosts. (The show should have closed out its run when Alex Trebek died.) But make no mistake: People who win at Jeopardy are, in fact, as smart as they look.

Related:

Today’s News

- Memphis officials released video footage showing the encounter with police that led to the death of Tyre Nichols, a 29-year-old Black man.

- After beating Tommy Paul in the Australian Open semifinals, the tennis player Novak Djokovic is on track to win a 22nd Grand Slam title, which would equal Rafael Nadal’s record.

- A judge released footage of the moment Paul Pelosi, the husband of Representative Nancy Pelosi, was attacked in his home.

Dispatches

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

Asteroid Measurements Make No Sense

By Marina Koren

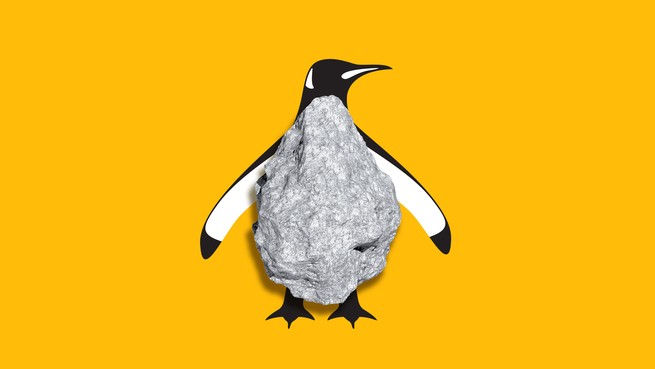

A couple of newly discovered asteroids whizzed past our planet earlier this month, tracing their own loop around the sun. These two aren’t any more special than the thousands of other asteroids in the ever-growing catalog of near-Earth objects. But a recent news article in The Jerusalem Post described them in a rather eye-catching, even startling, way: Each rock, the story said, is “around the size of 22 emperor penguins stacked nose to toes.”

Now, if someone asked me to describe the size of an asteroid (or anything, for that matter), penguins wouldn’t be the first unit that comes to mind. But the penguin asteroid is only the latest example of a common strategy in science communication: evoking images of familiar, earthly objects to convey the scope of mysterious, celestial ones. Usually, small asteroids are said to be the size of buses, skyscrapers, football fields, tennis courts, cars—mundane, inanimate things. Lately, though, the convention seems to be veering toward the weird.

Read the full article.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

Read. These books to read when you’re pregnant go beyond the standard guidebook to offer generous insight and reassurance.

A new oral history paints a vivid picture of life on Rikers Island, America’s most notorious jail.

And check out some cozy mystery series to keep you warm.

Watch. Poker Face, on Peacock, features Natasha Lyonne as a fun-to-watch crime-solving waitress.

If you’re in the mood for a movie, work through some of the Oscar-nominated front-runners.

And there’s always our foolproof list of 13 feel-good TV shows to watch this winter.

Listen. Spend time with the music of David Crosby, who died this month—and who was never a typical hippie, despite being one of the movement’s founders.

Play our daily crossword.

P.S.

Speaking of game shows, one of the television joys of my early teenage years was to come home from school and catch the old Match Game, in which ordinary Americans and show-business folks tried to finish each other’s sentences without being too dirty for the network censors. I stumbled across it on my Roku recently, and now I am mesmerized all over again by the great Gene Rayburn and his rotating cast of wiseacres.

Match Game was, for its time, a bit blue: Many of the clues were meant to sound naughty and designed to lead contestants to say “boobs” or “tinkle” or something. Today, it’s a joy to watch because it’s so quaint. (This is the show, after all, where it was ostensibly scandalous that people were skating the edge of outing Charles Nelson Reilly as gay, including wink-wink jokes from Reilly himself.) The celebrities—some of whom were big 1970s stars—are clearly having a ball; there were rumors of some boozing during the dinner breaks, and it shows. Watching Match Game in 1973 was like listening in on an adult cocktail party; today, it’s like a visit to your favorite bar full of characters, a kind of real-life Cheers masquerading as a game show. If nothing else, tune in for a look back at the Good Old Days, when people dressed like their home appliances in a riot of autumn rust, harvest gold, and avocado green.

— Tom

Isabel Fattal contributed to this newsletter.

watch searching 2 missing full movie